Independence with the Movable Alphabet

In so many classrooms I see children using objects and pictures with the movable alphabet. I usually also see that the child is not terribly interested in using the movable alphabet. It is often something they are supposed to do and not really what they want to do. I also don't see any stories or phrases being written with the alphabet. They are stuck on single words.

If you observe in a classroom like this, you'll probably notice a few things that are missing, particularly from the spoken language presentations.

1. Learning that they have something to say

First, the children are not given lessons on how to turn their thoughts into verbal expressions. A key lesson for this is conversations at a picture. In this lesson, you go to one of the beautiful pieces of art your have framed in your room...and swap out every month or so... and say, "I love this picture. I see so many things in it. What do you see?" Of course, this extends beyond artwork to everything of interest in the room, plants, pets, looking out the window, etc. The purpose is to give children practice in turning their thoughts into words. This also happens when we tell true stories (optimistic ones about our daily life) and encourage children to share theirs in natural conversations. The question game is another way to practice this skill. Use this whenever there is a little news in the classrooms. For example, you go on a field trip to the farm. Before the field trip, you have a little news period to briefly talk about your upcoming adventure. After the trip, you have question periods where you gather a small group of children and say, "Remember our trip to the farm? What animals did we see?" Continue asking for the children to recall and express other details from the shared event. Do this often for any shared event that comes up.

When you first present the alphabet, use it to write about something fun and interesting. For example, tell the child, "This morning my dog licked my face! I want to write that down." Then start sounding out words and writing them down. You can just hit the highlights (like dog likt fais) or hit every word... follow the child.

2. Hearing all the sounds in a word

I heard Lynn Lawrence give the most amazing presentation of the sound game (I Spy) at a NAMTA conference years ago and suddenly it all made sense. We all know that the first step is to help children notice the beginning sounds in words and to do it with something obvious (like "I'm thinking of something in my hand that starts with mmmm" when there is only one thing in your hand). But when we switch to focusing on ending sounds, we should NOT drop the beginning sound. Instead, for this level of the sound game, we say "I'm thinking of something on the rug that starts with rrrrr and ends with kkkk." Rock. Rather than adding in to much difficulty, this simply directs the attention to a new part of the word. For middle sounds, we say, "I'm thinking of something on the rug that starts with rrrrr and ends with kkkk." Once they find the rock, we ask, "Are there any other sounds in the word rock?" Finally, in the fourth level of the sound game, we ask them to identify all of the sounds in a word (like basket). They need to have success at each level before moving on the next level and they need to consistently be able to hear all the sounds in a word (level 4) before they will succeed with writing any word they want to write with the movable alphabet.

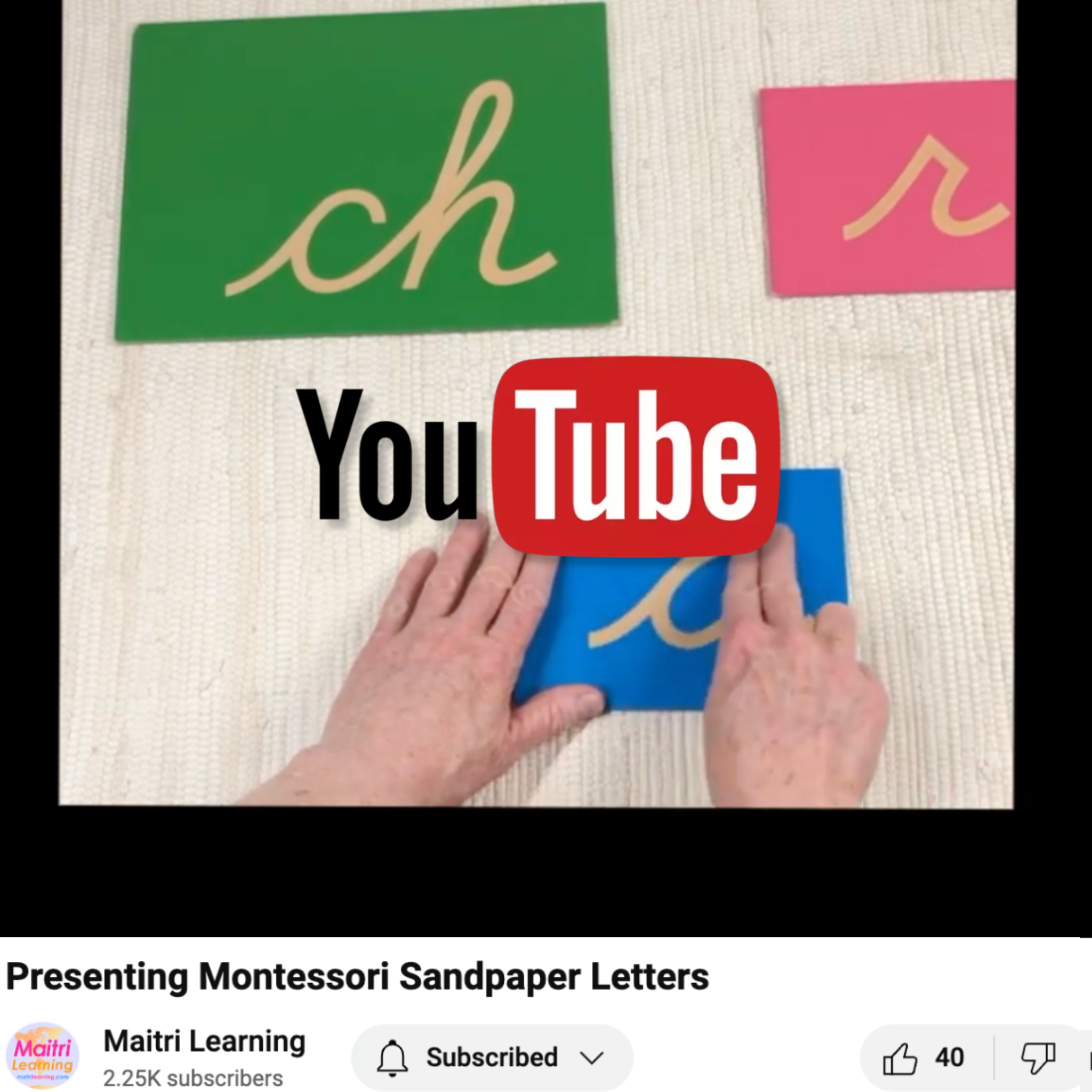

3. Knowing all the sandpaper letters, including phonograms (pink, blue, and green letters)

We are so eager to send home a picture of the children "writing" words (big scholarly work that the parents can finally get on board with) that we often jump into the alphabet too soon. The children really need to have success with almost all of the letters, including the phonograms, before we should introduce the movable alphabet. Why? Because the alphabet is a tool that frees them to explode into writing! They can't explode into English unless they know all of the symbols used to write it... you can't make oy, or, sh, or th with only one letter! Our adult minds think phonograms are complicated and should come later than individual letters but this is just not how it works for the absorbent mind. The young child sees the phonogram as a symbol, just like an individual letter. If you are using cursive, this is even easier for the young brain to understand (yet another reason to use cursive). So, the first few times you give a sandpaper letter lesson, choose two consonants and one vowel. But by the third or fourth time, you should choose one consonant, one vowel, and one phonogram. Then, go forth forever more with one of each.

4. Presenting how to use the box

Some children are just plain intimidated by the complexity of the box that houses all those letters. Remember, children are perfectionists. If they believe they can't succeed at something, they are not going to try! So, the first lesson with the alphabet is always "How to use the box." This includes carrying the box to/from the shelf, opening and finding a good place for the lid, finding letters, taking letters out one at a time, and putting letters back one at a time. I saw one child repeat this lesson excessively. The guide in her room explained that she had given her the "how to use the box" lesson over a week ago and that the girl did it every day since with greater and greater fluidity. When she was finally shown how to write about something, she soared.

So, observe your children and see what's going on in your room. Then, remedy the situation. If you've been off track and the kids are stuck on objects/photos instead of using their own ideas, just take the alphabets off the shelves for a week or two and start fresh. It is so totally worth it.

FYI, here's our movable alphabet lesson plan,

2 comments

Guide to encouraging literacy independence through rich back-and-forth exchanges, sound awareness, and purposeful use of the movable alphabet!

Sudha Acadamey

Very good

Pamonphop Kiniphan

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.